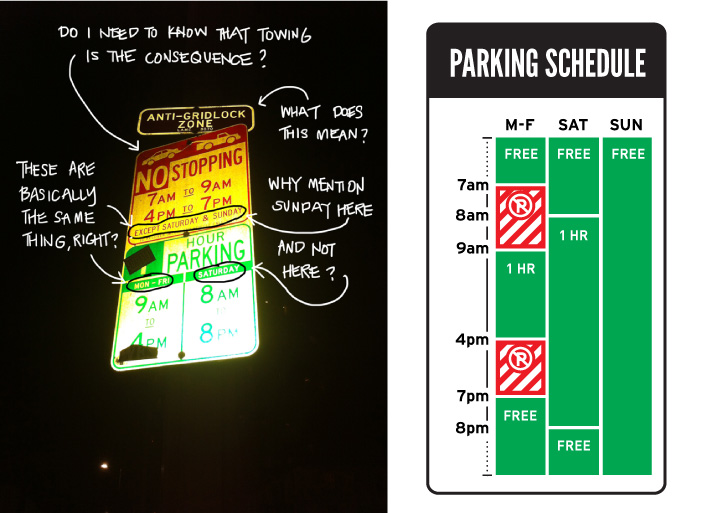

On a winter evening in 2014, Nikki Sylianteng got a parking ticket. It wasn’t a surprise. This was in LA where the city collects around $140 million from tickets annually. Sylianteng’s $95 parking ticket wasn’t significant and it wasn’t a surprise. But what happened next was.

When designing security capabilities, we have two aspects to consider:

• The paths people take to complete work – number of steps, familiarity, and friction of each step

• The choices people make during work – number of choices, predictability, and cognitive load

I argue that security can improve people’s work. Make it easier. Make it faster. I often get pushback on this argument, and for good reason. A very real problem is that security teams don’t have good visibility into the path and the choices. Even more worrisome, we don’t get good feedback when things are difficult or when security controls are making them worse.

Millions live in LA. Hundreds of thousands get tickets in LA. One person gave feedback with a solution.

Why? It is the same reason the workforce tolerates bad security controls: habituation. People get used it. They become blind to the annoyances along the path they have to take to complete their workflow. Listen for these tell-tale phrases:

• That’s just the way the world works

• We’ve always done it this way

• Things could be worse

That’s an indication of a workflow security may be to improve while increasing security. There lies habituation. There lies unnecessary steps or choices. There lies an opportunity to improve the path. But we need a partner on the inside, someone who can see beyond the habituation, someone who has what’s called beginner’s mind.

This is what drew me to the story of Sylianteng and her parking ticket. (Listen to Nikki Sylianteng tell her story herself here.) She didn’t accept the ticket. She couldn’t accept the way the parking signs were. She launched To Park or Not to Park and radically redesigned the parking signs. She has since created tools that anyone can use to create their own simplified parking signs.

Imagine our security goal is parking enforcement. Our control, the parking sign. Four million people in LA see the signs. Some follow them. Others don’t. Only one person actually says this is a problem, and takes it on themself to correct the problem. Do we embrace this person? Well. We should. According to Nikki Sylianteng, her new approach “has shown a 60% improvement in compliance and has pilots in 9 cities worldwide.”

Find those with a unique combination of beginner’s mind and desire to make a change. Embrace them. They are your security champions, and by working together, leaps in adoption and compliance are possible.

This article is part of a series on designing cyber security capabilities. To see other articles in the series, including a full list of design principles, click here.