“Develop people, develop security.” That was our tagline for the SimWitty team. The order reflected our values and simplified decisions. What to prioritize, developing a skill in a teammate or getting a release out the door? When develop people comes first, the answer is clear.

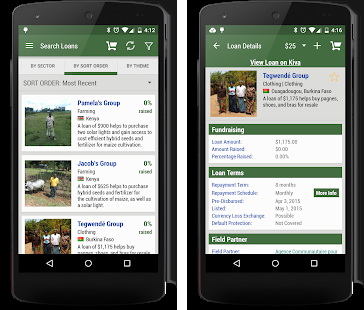

“Make a loan, change a life.” That’s Kiva’s tagline. Kiva has significantly more impact on broader social issues than SimWitty ever had, and it’s barely a comparison. There is one thing both have in common: values reflected in slogans resulting in decisions.

Kiva had a challenge. While its goal was to change lives through loans to small businesses, most businesses weren’t completing the application. The conversion rate was less than 1 in 5. Kiva looked to make design changes to simplify the application process. Many suggestions were made. One suggestion was particularly counter-intuitive to the point of being controversial: give small businesses a deadline.

“The founder was appalled. By giving customers a deadline, the company would have to deny service to people who missed that deadline. Denying service, the founder argued, was not a part of their company values,” wrote Kristen Berman, founder of Common Cents and Irrational Labs, who championed the design work for Kiva.

Security leaders must bring a degree of clarity to their team. Our values must be clear. Our criteria must be clear. And how we’ll try things and evaluate decisions must be clear. For Kiva, that meant changing lives through access to capital, with the number of people who complete loan applications as one measure. What does it mean for a security team?

Berman’s team went to work and experimented with deadlines. The number of completed applications went up. They experimented with incentives for early completion. Application rates went up further. More small businesses than ever were completing applications, resulting in changing more lives than ever. The decision to move ahead with the approach was clear.

This series has covered security programs reflecting strongly held corporate values. It’s equally important that a security leader have strong personal values, and that these values are reflected within the team. As Kiva’s example illustrates, there are times when options, on the surface, run contrary to our values. The path forward is to have a clear definition of success within those values.

Clarity enables experimentation and innovation while remaining true to what we believe in. Security leaders design capabilities and lead teams that reflect their personal values.

This article is part of a series on designing cyber security capabilities. To see other articles in the series, including a full list of design principles, click here.